The 1920s novel “The Virgin and the Gipsy” shows us something remarkable: what real sexual liberation could have looked like. And when you understand this, you realize that the sexual revolution of the 1960s and 70s completely missed the point.

In the novel, we meet a gypsy woman who embodies authentic female sexuality. She’s not “liberated” in the modern sense – she’s married, lives traditionally, doesn’t sleep around. But she possesses something far more powerful: an undiminished, natural feminine sexual energy that makes the “respectable” English people deeply uncomfortable.

This discomfort isn’t because she’s doing anything scandalous. It’s simply because she exists in her full feminine power without apology. She doesn’t suppress it like the proper English ladies, but she also doesn’t perform it or throw it around cheaply. Her sexual energy remains concentrated and whole, like a well of deep water.

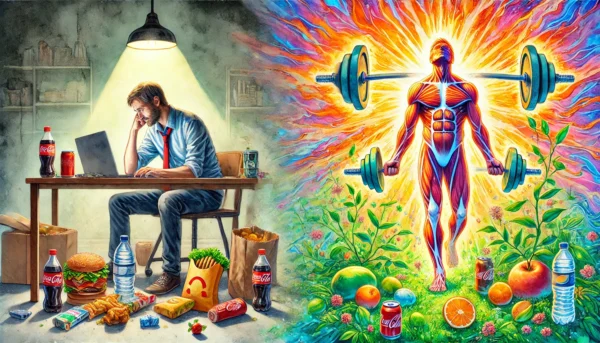

When the sexual revolution came along, we had a chance to understand and embrace this kind of authentic sexuality. Instead, we went in exactly the wrong direction. We created a culture that measures sexual liberation by how many partners you’ve had, how casually you can treat sex, how “free” you are from all boundaries.

But real sexual power doesn’t work like that. The gypsy woman in the novel shows us that true sexual energy becomes more powerful through natural containment, not through dispersal. She’s like a river flowing in its proper channel, not water spilled across the ground.

The sexual revolution replaced Victorian prudishness with something equally dishonest: the idea that scattering your sexual energy around equals freedom. We traded shame about sex for cheapening of sex. Neither one comes close to the authentic sexuality that Lawrence was writing about.

This matters because we’re still living with the consequences. Young women are taught that sexual empowerment means racking up experiences and treating sex casually. But look around at our hook-up culture – does anyone seem genuinely sexually empowered? Or are we just acting out a different kind of sexual performance, one that diminishes rather than enhances our natural sexual power?

The gypsy woman shows us another way. Her sexuality isn’t about what she does – it’s about what she is. She doesn’t need to prove her sexual power through actions because she simply inhabits it fully. This is what real sexual liberation would have looked like: not freedom to do whatever you want, but freedom to be who you truly are.

We’re still waiting for this genuine sexual liberation. Maybe it’s time to stop confusing sexual freedom with sexual dispersal, and start understanding that real sexual power comes from keeping our essential nature whole and undiluted.

The sexual revolution was a missed opportunity. But it’s not too late to understand what authentic sexuality actually means.